Cruciate Disease Explained

What is cruciate disease?

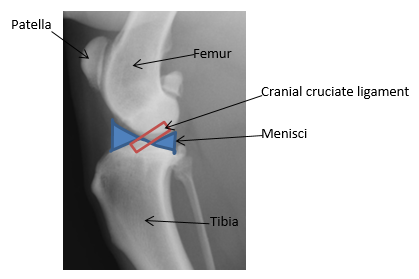

In the stifle (knee) of the dog two ligaments called cruciate ligaments hold the femur (thigh bone) to the tibia (shin bone).

In humans this ligament (ACL) can rupture for example when skiing or playing football. In dogs this is not usually the case, instead the cranial cruciate degenerates over time, this means we have to treat it differently as there is no ligament left to repair.

This occurs for many reasons but certainly genetics play a large role as we see this condition most commonly in large to medium breeds such as Labrador Retrievers, Golden Retrievers and Rottweilers. We do see it in small breeds as well for example West Highland White Terriers. It can occur from 6 months of age onwards.

If your dog is obese they are FOUR times as likely to get cruciate disease.

What are the clinical signs?

The signs to start with can be subtle as a few of the fibres tear, there may be minimal to no lameness but then as more fibres tear and the knee becomes unstable the lameness deteriorates.

The knee is unstable because the bones (femur and tibia) can now rock back and forth during walking. This can be sudden, often during normal activity, the dog can become acutely lame and may not even want to weight bear on this limb. Often they will sit with one leg out and occasionally you can hear a clicking noise.

If both knees are affected at the same time this can almost look like the dog is paralysed in both hindlimbs because they do not want to weight bear.

How is cruciate disease diagnosed?

An orthopaedic examination including gait analysis and then palpation of the stifle can detect the instability (cranial drawer/tibial thrust tests).

Occasionally sedation is required to feel this instability.

Xrays are taken of the stifle to show signs of osteoarthritis, to rule out other diseases and to allow surgical measurements/planning. Very early cases can be challenging to diagnose and may require exploratory arthroscopy (key-hole surgery) to examine the cruciate ligament. Sometimes joint fluid samples are required to examine the fluid for other diseases (e.g. immune-mediated diseases, infection and rheumatoid arthritis).

In the same way that your doctor can refer you to a consultant, your local vet may refer your pet to a specialist orthopaedic surgeon who sees this condition on a regular basis, can assess your dog, guide you with the best treatment for your dog and has advanced surgical techniques and equipment available to them.

You might also be interested in:

How do we treat cruciate disease?

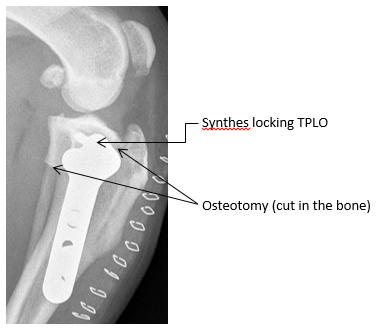

Prompt diagnosis and treatment are vital to prevent further damage to the cartilage of the knee (from the bones rubbing each other). There are numerous techniques and certainly very little dogs which do not have a steep tibial plateau may do well with rest and anti-inflammatories. Larger dogs generally do not respond to this and do require surgery. We offer two techniques and in specialist hands dogs generally respond very well to this treatment. There is the “extracapsular technique” which uses nylon to temporarily stabilise the knee or we can use techniques that alter the bone to neutralise the forces in the knee (so it no longer rocks back and forth). This is called a TPLO (Tibial Plateau Levelling Osteotomy). Recent research has now shown this method to give excellent results.

At Vets Now Referrals we use the Synthes locking plate technology for the TPLO procedure, this provides mechanical advantages and reduces the complications of TPLO, for more information please click on this link www.tploanswers.com. The advantages of TPLO are that it can be used in all sizes of dog, even the Giant breeds and there is an early return to function. There is a greater cost to perform a TPLO due to the complex nature of the surgery and the cost of the implants. Whichever technique is used it is vital that we look inside the joint in a minimally invasive way; this is to examine both cruciate ligaments and the menisci (cartilage shock absorbers). Often the menisci are torn and need to be trimmed or removed. If the joint is not explored properly this can leave a painful joint and lameness.

What do I need to do once my dog has had a surgery?

It is imperative that your dog does not lick the wound until the stitches or staples are removed at 10-14 days, during this time a buster collar should be worn. This reduces the risk of infection.

We will guide you with regards to any post-operative medications that your dog should receive.

Most importantly your dog will need to be strictly rested for approximately 6 weeks either in a small room or large cage, with absolutely no jumping, playing, slippery floors or stairs. After this time we shall reassess and repeat xrays (if your dog has had a TPLO), we shall discuss and guide you on how to rehabilitate your dog back to normal activity.

It must be noted that arthritis caused by cruciate disease happens in every case but most dogs do still return to their normal activity. The arthritis is best managed by keeping your dog a lean weight.

With close guidance from your veterinary surgeon in conjunction with a specialist Orthopaedic surgeon we will be able to help you decide what is the best way to manage your dog’s cruciate disease.